By TOM MOLANPHY Via 48hills.org

In a land of drought and pollution, can environmental harmony be built into Build Back Better?

Last week, millions of baby salmon completed their long journey from the Central Valley by being dumped by the truckload into San Francisco Bay. Due to the impact of California’s ongoing drought on the highly modified Sacramento River, the juveniles could no longer swim from their birthplace to open ocean, so the trucks were called in to help them make their way.

The vehicle-assisted release highlights a crisis that some experts are calling infrastructural.

Oxford defines infrastructure as “the basic physical and organizational structures needed for the operation of a society or enterprise.” But some Bay Area environmentalists and wildlife professionals hope the Biden Administration’s federal infrastructure proposal offers an opportunity to consider the infrastructure that came before the roads and bridges that the term evokes.

Namely, the soil, water, air and all of the flora and fauna that sustained life in a cooperative balance before the disruption of the Anthropocene era.

“The San Francisco Bay Delta provides water to 2/3 of the people living in the state, and that water is supplied by Central Valley rivers, first and foremost among them the Sacramento River and its tributaries. That’s all infrastructure,” said John McManus, President of the Golden Gate Salmon Association, who witnessed the salmon drop firsthand.

For advocates like McManus who want to preserve natural resources, it’s less of a question of the restoration of infrastructure and more of the restoration of a healthier relationship with our natural resources. In short, “Build Back Better” should include giving Mother Nature a seat at the drafting board.

McManus uses a different metaphor: “When it came time to cut the pie up [in terms of resource allocation], humans elbowed any consideration for nature away from the table,” McManus said. “Basically took the whole pie. In wet years, there’s more pie than humans can eat. But most years, the wildlife experience a drought just because of how the pie’s been allocated.”

There’s no argument that the built infrastructure isn’t failing. The 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure gave the US system a C-. McManus believes our management of the natural infrastructure that makes everything else possible is even worse.

“The story of having to truck these fish is the story of us getting an F on the report card for trying the infrastructure part as well as some level of stewardship over the natural system. We failed in the latter.”

Whether it’s restoring nature or adding man-made infrastructure, one of the essential questions for any planner is, what future are you building for? Once in a generation natural disasters like fires and floods now happen more regularly due to climate change.

“With sea level rise, if you drive out on the delta on top of the roads on the levies, you look down and see dry land below sea level. These levies could be threatened as sea levels rise, so they might need to be beefed up, too.”

*****

South of San Francisco Bay and north of Santa Cruz, the Amah Mutsun Land Trust is working to restore another native ecosystem: coastal prairies. In collaboration with State Parks and Pie Ranch, AMLT will be propagating, planting, and harvesting seeds for 120,000 native plants to restore the habitat.

“Whenever people talk infrastructure, they mean dominating Mother Earth with bridges, dams, and highways that all break up bioregions,” AMLT Chairman Valentin Lopez said. “All they’re doing is looking at infrastructure that serves a select portion of human beings.”

Native American cultures have a long history of living in harmony with the land, as well as their own longstanding ideas about infrastructure. And both McManus and Lopez agree that some human infrastructure, such as dams, might need removal to help restore the natural infrastructure. (This summer’s closure of Point Reyes Beach to remove an ill-advised parking lot is another example where less human infrastructure is better.)

“Infrastructure is a whole system. The example of the coastal prairie is a good one,” Lopez said. “The Central Coast of California used to be a coastal prairie, top to bottom. It was one of the most biodiverse landscapes in North America.”

And Chairman Lopez believes the Oxford definition of infrastructure, at least in spirit, is in harmony with the Native understanding.

“Our coastal prairie system provided food, medicine, basketry, energy for cooking, materials for housing, bow and arrows for hunting. All the material that were needed for our people to thrive.”

The essential difference between the Anglo-European approach to infrastructure and the Native American approach can be summed up in one word: sacred.

“We think of Mother Earth as sacred. Whenever they talk about infrastructure today, who talks about restoring the scaredness of the land? What they talk about is dominating the land.”

“Sacredness is never a consideration whatsoever. That’s a big problem in the world we live in today.”

As far as which approach is more successful, Lopez doesn’t hesitate to point to the long history of the Native American system with pride.

“We maintained our infrastructure. That infrastructure was the native grasses. The forest. The rivers. The ocean. That was the infrastructure our people were responsible for managing and maintaining. And our people did that for 15-20,000 years or more.”

For the politicians who don’t know how to work the word “sacred” into an infrastructure bill, Valentin also offers tangible and pragmatic advantages for restoring coastal prairies in California, not least of which is to create a fire-resilient infrastructure during another brutal drought.

“By restoring the coastal prairie, we avoid the tremendous build-up of fuel loads for catastrophic fires. That can protect housing and schools and the other manmade infrastructure that’s there. (The benzene contamination of drinking water in Paradise is just one example of what megafires do to infrastructure that is not fire-resilient.)

“Our native plant infrastructure is more resistant to fires, floods, and drought, as well as disease. You get protection from flooding because you don’t get those tremendous mudslides with native plants in place. And then the biodiversity will follow.”

*****

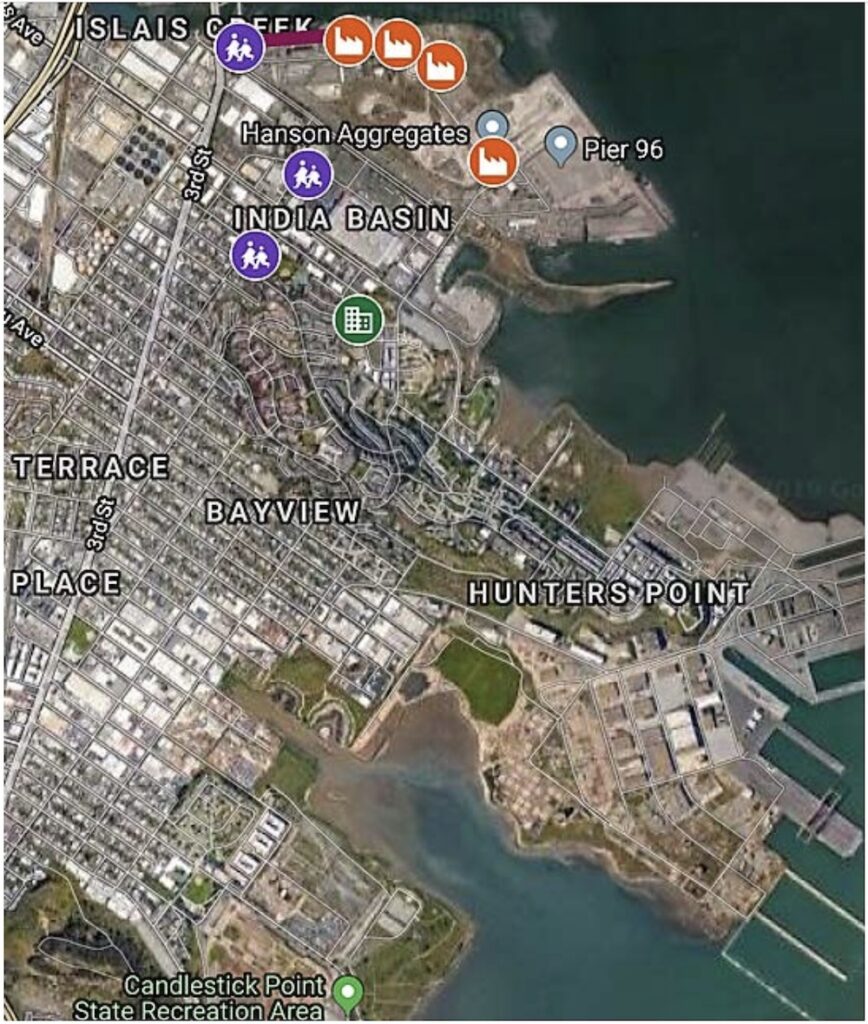

In San Francisco’s Bayview neighborhood, our fractured relationship with that original infrastructure, our need to dominate instead of inhabit, plays out with significant penalties on the least fortunate.

And for Greenaction Executive Director Bradley Angel, one of the biggest penalties involves what all modern infrastructure relies on: concrete.

“There are two huge concrete plants that have operated at the Port of San Francisco for years out of compliance and without permits,” Bradley said. “For years the community and Greenaction has been demanding for them to be shut down.”

In May of 2020, the Golden Gate Environmental Law and Justice Clinic released a study of the concrete plants in question, as well as the Bay Area Air Quality Management District’s enforcement of permits for these facilities. The results were damning.

“Some of these facilities operate in violation of Air District rules, either by emitting pollution without permits or by violating permit limits,” the study found. “Unquestionably, the facilities bear the responsibility for violating the law. The Air District, however, is also independently responsible to ensure that its permitting and enforcement programs properly regulate emissions from these companies.”

Environmental justice advocates warn that if restoring infrastructure only means replacing old bridges, roads, and tunnels with new ones, the businesses that manufacture the necessary material like concrete in industrials areas like the Bayview will continue to spew pollution into these underserved communities who a) rarely get the jobs to create this infrastructure and b) suffer from the creation of the infrastructure while reaping less of its benefit.

Even though Angel is glad the report came out, he still fears it will be business as usual for the Bayview. And that business as usual has led to some of the highest rates of asthma in the Bay Area.

“We forced them (BAAQMD) to announce a 30-day public hearing on whether to permit these facilities. But the reality is they have already made up their mind.”

Meanwhile, the feds will continue to argue what the definition of infrastructure should be. And whether it’s considering salmon or coastal prairies as an integral part of a resilient infrastructure, or really considering who benefits from the built infrastructure itself, one fact is clear: How we build back better will define what we’re made of.