Solutions – Improve: Habitat, Hydrology (water flows), and Hatcheries

Improve/Restore Habitat

We’ll never reclaim the 80 percent of historic salmon habitat behind the dams but there is lots of potential for improvement below the dams.

Improve Hydrology

Improve Hatchery Success

Improving/Restoring Habitat

Among other improvements, the salmon rebuilding plan stresses the need to restore areas along the edges of Central Valley rivers where baby salmon can safely feed, grow, and hide from predators.

Side channels, featuring lower velocity flows and overhanging trees and brush where insects cluster, have been lost in man’s effort to tame and hem in the rivers and streams. GSSA calls for restoration of these beneficial rearing areas.

There is good evidence that well fed baby salmon survive better than hungry, skinny, baby salmon. Baby salmon able to access remaining flood plains see higher survival and better chances of reaching the ocean.

Aerial photographs make clear that many former parts of the Central Valley river beds, now dried out behind dikes and levees or plugged by gravel, can be restored by moving a little earth. The greatest opportunities to restore side channels and rearing areas, as called for in the GSSA plan, are in the upper parts of the Sacramento, Feather, American and Yuba rivers. The Sutter bypass, which is basically a flood plain currently available to Butte Creek, and sometimes Sacramento and Feather River salmon, could be made more accessible to runs from the Sacramento, Feather and Yuba rivers with minor modifications.

The Yolo Bypass west of Sacramento holds the greatest potential rearing area in the Central Valley. Its value for growing baby salmon is so high that the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) required state and federal water managers to modify barriers separating it from the Sacramento River to make it more accessible in the 2009 biological opinion. GSSA echoes this call as a very important action identified in our salmon rebuilding plan. Flood control barriers that separate the Sacramento River from the Yolo Bypass can be lowered to allow this. In addition to rich feeding grounds for juvenile salmon, the Yolo Bypass drains to the western Delta at a point safely beyond the area where the Delta pumps can pull baby salmon off their natural migration course. This provides a major benefit to baby salmon exiting the Central Valley through the bypass instead of through the Delta.

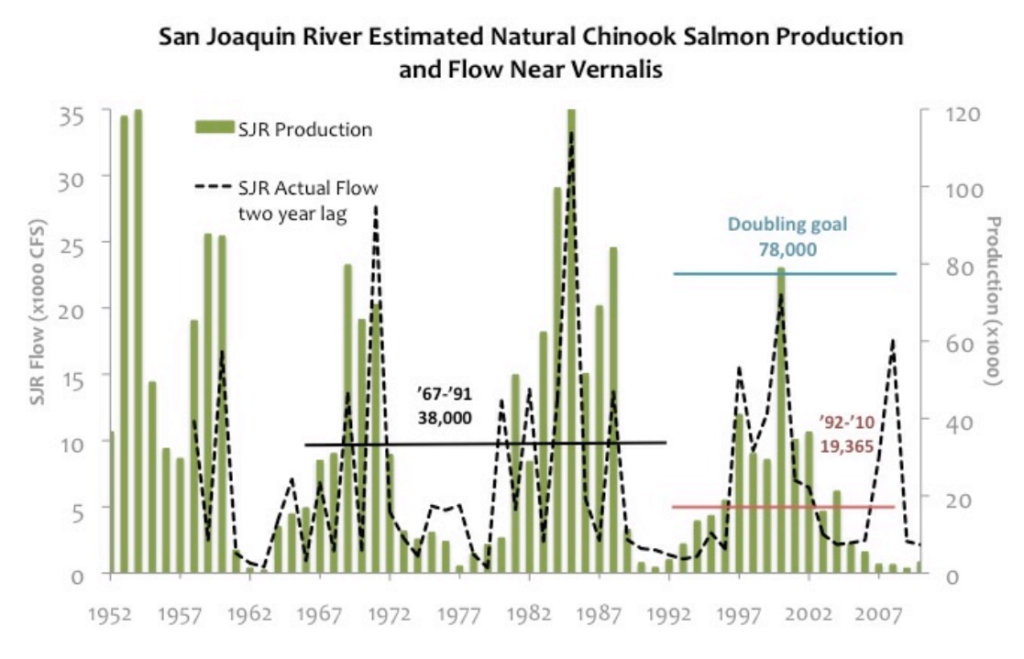

Hydrology – Improving flows

We always see a resurgence in salmon runs two years after a wet winter/spring because baby salmon survive at much higher rates during big runoff years, proof positive that lack of river flows is the main problem for salmon. Reservoirs can be operated (as they are on the Columbia and Snake Rivers in Idaho, Oregon and Washington) to release adequate water in the spring to aid the downstream migration of the baby salmon. Not only do we usually fail to do this in California, but when these spring water releases are most needed (in drought years), water managers are least inclined to share water for salmon.

Dams capture the natural runoff and block river and stream flows that salmon have evolved to depend on. In very wet years there’s enough rain and snow runoff coming down streams below dams to mimic the pre-dam condition, but not so in dry years. That’s when it’s needed most. To date, federal requirements designed to protect Central Valley salmon have always come up short by not including such a requirement.

Salmon don’t need high flows all the time, only during part of their life cycle.

Water distribution in the Central Valley is driven partly by the needs of federally protected species and partly by the demands of water contractors who take water from state and federal water projects. These needs often run counter to each other. For the most part, flows and temperatures are only managed for fish when federal law requires it. For instance, the 2009 salmon biop required a portion of the upper Sacramento River to be maintained at no more than 56 degrees from June 1 through October 1 to aid spawning winter run salmon. But too often, fall run salmon, which spawn from September through December, spawn in flows above 56 degrees, which kills their eggs. Similarly, reservoir releases have to be maintained at a steady level during that same June 1 through October 1 time period so that winter run redds (salmon egg nests) remain inundated. Too often, come October 1, reservoir releases are cut drastically. This often leads to dewatering of fall run redds and massive loss of fertilized eggs.

Improving Hatcheries

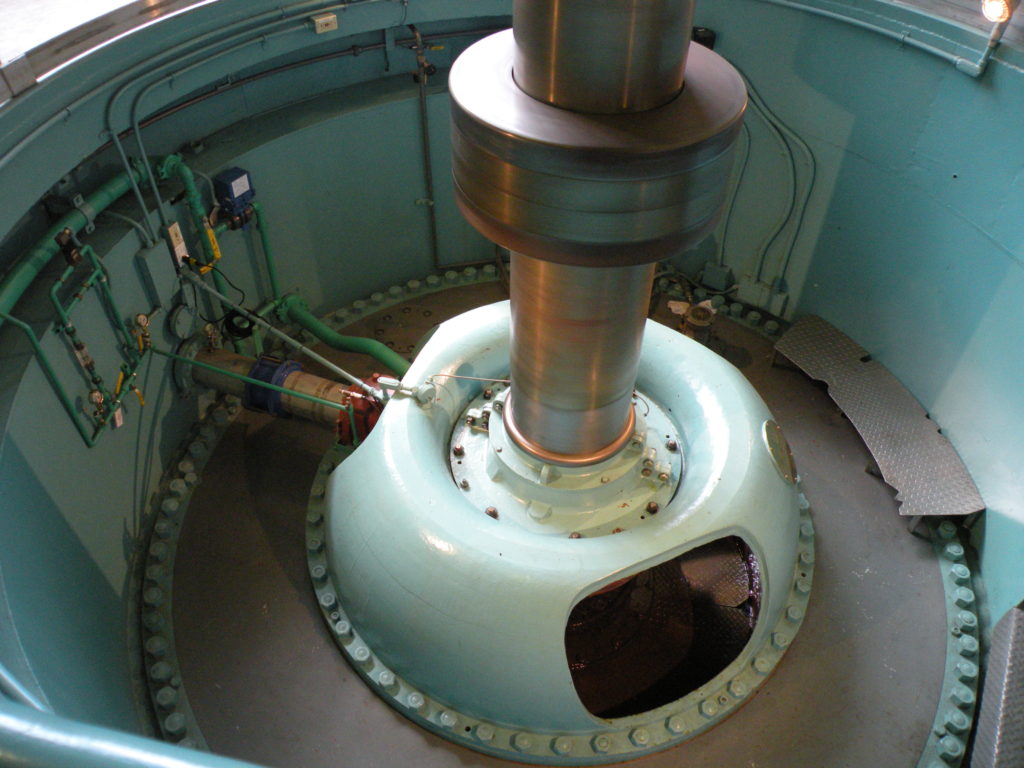

As mitigation for putting the dams in, which dramatically cut freshwater flows and cut off 80 percent of salmon habitat, the state, and federal government installed hatcheries. In the 1990s hatchery production was reduced. With the implementation of some innovative and creative measures, hatchery efficiency is improving.

GSSA’s Plan

To address these and other problems, GSSA worked with fisheries biologists and state and federal fish agency experts to develop a salmon rebuilding plan. The plan currently has over 20 projects that will strengthen Central Valley salmon runs when implemented. We also remain deeply engaged in a defensive mode to hang on to the water that still exists in Central Valley rivers, without which, salmon can’t survive.

The projects were selected because they rebuild both wild and hatchery salmon runs and can be implemented at early dates, mostly affected by funding availability and permit approvals. The projects call for fixes both in the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, their tributaries, and in the Delta and in hatchery practices. They are all addressed at improving some aspects of habitat, hydrology (river flows) or hatcheries.

- Modifying predator hotspots by eliminating predator hiding places or giving the baby salmon places to hide in predator locations

- Reconstructing side channels that provide baby salmon safe rearing areas

- Reconnecting floodplains that provide baby salmon rich food resources

- Using pulse flows in the rivers and tributaries to move smolts and fry past predator hot spots and to inundate floodplain rearing habitat

- Improving the archaic pump salvage system in the Delta to reduce losses at the Delta pumps

- Adding spawning gravel for wild salmon throughout the Sacramento River basin

- Changing reservoir operations that currently dewater wild salmon eggs leaving them high and dry when the flows are cut

- Releasing hatchery smolts past the Delta and/or river hazards and closer to the ocean while also minimizing straying

GSSA has engaged water managers and water districts to seek modifications to the practices that harm salmon. In years flush with water, it’s generally easier to find common ground. In times of drought, it’s much harder.

Some projects have been completed or are well on their way. You can read about some of the projects that have been implemented and are now aiding in salmon restoration in: