By Cariad Hayes Thronson via SF Estuary Magazine

As California stares down the barrel of yet another dry year, alarm bells are already ringing over conditions in the Delta. Environmental groups, fishermen, tribes, and a host of others are calling on the State Water Resources Control Board to complete and implement a long-delayed update to the Water Quality Control Plan for the Bay and Delta (Bay-Delta Plan), to protect the imperiled ecosystem. At the same time, plans for a structure with the potential to divert more water than ever to southern cities and farms are creeping ahead.

By law the Bay-Delta Plan — which establishes minimum flows through the Delta from the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers and their tributaries — is supposed to be reviewed every three years; however, parts of the plan have not been amended since 2006. “By some measures we are now 12 years into a triennial review,” says San Francisco Baykeeper’s Jon Rosenfield.

In 2018, the State Board seemed to be on the verge of completing the update: it adopted instream flow objectives for the lower San Joaquin River and its tributaries (known as Phase 1), calling for 30% to 50% of unimpaired flows, and released the framework of a similar plan for the Sacramento River and flows into and through the Delta (Phase 2). However, in an effort to avoid time-consuming litigation and water rights adjudications, the state halted further work on the update, hoping to reach “voluntary settlement agreements” with water users.

These agreements might permit lower instream flows in exchange for “non-flow” measures such as habitat improvements to meet environmental goals that include the Delta Reform Act’s requirement to double populations of endangered Chinook salmon. To date, water users and state agencies, including the departments of Water Resources and Fish and Wildlife, have proposed several voluntary agreement (VA) frameworks; however, none have been submitted to the Board for approval.

“The last public presentation of a voluntary agreement proposal that we saw was in February of 2020,” says Rachel Zwillinger of Defenders of Wildlife, one of the NGO’s involved in the discussions.

The stalemate is due at least in part to political skullduggery around new biological opinions (BiOps) for endangered Delta species that would allow increased diversions from the Central Valley Project and deliver on then-President Trump’s promises of more water for agricultural interests. In July 2019, federal scientists completed work on new BiOps (which are required by the federal Endangered Species Act and govern joint operations of the Central Valley Project and the State Water Project) that had been initiated during the Obama administration. Their report found that increased pumping would harm populations of several protected species, including winter-run Chinook, steelhead trout, and orcas, which feed on salmon in the ocean.

However, the U.S. Department of the Interior, under then-Secretary and former Westlands Water District lobbyist David Bernhardt, suppressed the report, and the team that produced it was replaced with a different team charged with reversing the findings. Final BiOps released later that year found that the Trump plan would not jeopardize endangered fish; California and several environmental groups then sued the administration over the rolled-back protections. (Newly public documentary evidence in the state’s suit seems to confirm what many observers had suspected: the final BiOps process was politically tainted, with scientists sidelined and science buried.) Water users had hoped to use the Trump BiOp as the baseline for voluntary agreement negotiations, but walked away from negotiations when the suit was filed.

Recent State Board meetings have included numerous calls from stakeholders for the Board to move forward with the water quality plan, and one Board member has called for an update. However, upcoming meeting agendas do not include items related to the plan.

“What we’ve seen over the last year is that the Board is just waiting and waiting and waiting for a voluntary agreement that may never arrive,” says Zwillinger. “And in the meanwhile, we’re watching the estuary continue to crash and endangered species sliding closer to extinction.”

Indeed, deeply ominous signs abound. Recent fish sampling programs found only a small handful of Delta smelt, and scientists are openly discussing 2021 as the year the species goes extinct in the wild. As for salmon, the pre-season ocean abundance forecast is only about 271,000 fish—about 200,000 less than in 2020—indicating that fishermen will face significant restrictions this year, according to John McManus of the Golden State Salmon Association. And last year the Delta was plagued by some of the worst harmful algae blooms ever seen, in part because of inadequate freshwater flows.

“I just can’t stress enough how bad the water quality was here this last year,” says Restore the Delta’s Barbara Barrigan-Parrilla.

Some believe that with a new, much more environmentally friendly federal administration in charge, the water users may have an incentive to come back to the table. One of President Biden’s first actions in office was to initiate a review of Trump administration regulatory actions, specifically identifying the Delta BiOps as warranting quick evaluation. “I understand the water districts are preparing a new VA proposal,” says Rosenfield. Some are suspicious of their motivation, however.

“A fresh VA proposal that may result in negotiations with the state probably won’t do anything other than to create more delay and keep the State Board from moving forward with its regulatory responsibilities in updating the Bay-Delta water quality plan,” says McManus.

Defenders of Wildife’s Zwillinger thinks it’s time for the Board to make clear that it’s done waiting, and that it plans to protect the estuary — with or without a VA. “It’s very hard to see how the parties will come to the table sufficiently motivated to actually make a deal and cross the finish line without the Board moving forward on updating water quality standards for the Delta,” she says. “There’s no incentive for anybody to have a real conversation about a voluntary agreement unless there is a meaningful threat that the Board is going to move forward with its process.” Efforts to get a Board comment for this story were unsuccessful.

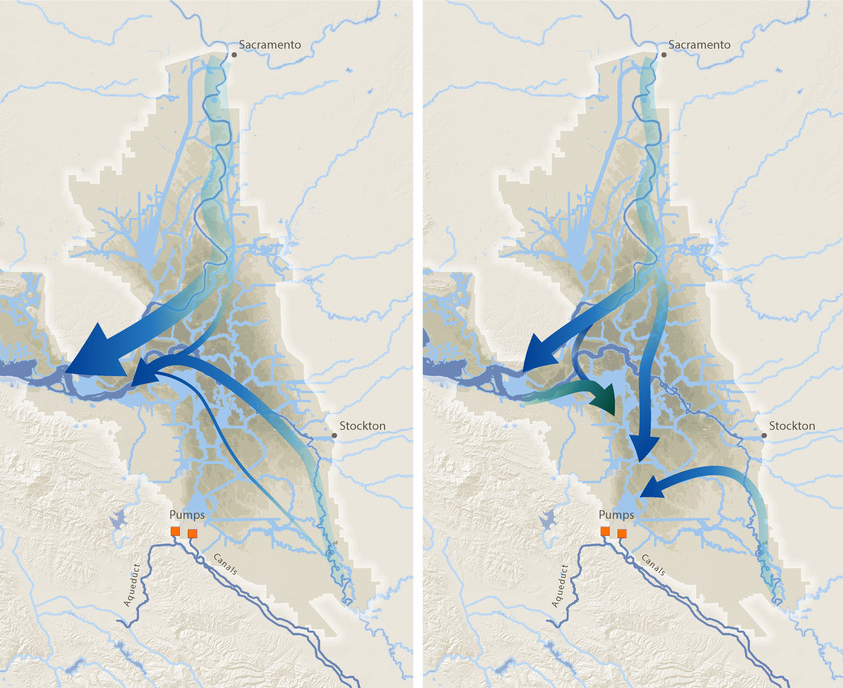

The water quality plan is not the only process that Delta stakeholders are watching warily. Last year, the Department of Water Resources (DWR) began drafting environmental documents for yet another version of the decades-old scheme to take freshwater out of the Sacramento River and send it directly to the State Water Project, bypassing the Delta. DWR and State Water Project contractors maintain that the conveyance is needed to ensure a reliable water supply in case the Delta’s aging and fragile levees succumb to sea-level rise or an earthquake. The last effort, known as the California Waterfix, included two tunnels under the Delta and died at the end of the Brown administration; it has since been resurrected as a single tunnel and christened the Delta Conveyance Project.

DWR is evaluating two different alignments and facility sizes capable of pumping between 3,000 and 7,000 cubic feet per second. A Design and Construction Authority (DCA) established by the public water agencies that would build the project is conducting engineering and design work, as well as public participation and stakeholder engagement activities.

Barrigan-Parrilla serves on the DCA’s Stakeholder Engagement Committee, “not because we support the project, but to make sure that [local] people and groups are not harmed if the project work comes to pass,” she says. She believes the entire project framework is deeply flawed in that it fails to address the Delta’s most pressing issues. “We still have real concerns that because this framework hasn’t been set up correctly, what we’re going end up with is an end product that really isn’t going change any of the dynamics for people in the community. And more importantly, it’s not going to save the Estuary, it’s not going to save fisheries, and it’s not going to protect us from flood.”

Although few details about the size, pumping capacity, and operations of the tunnel have been finalized, Zwillinger says the most basic problem is one of sequencing, arguing that the water quality plan should be completed before any planning for a tunnel.

“We need the water quality protections for the Delta first, because that’s what tells us how much water we need to flow into and through the Delta to keep the ecosystem healthy,” she says. “Once we know that, we can figure out how much how much water a new Delta conveyance facility can safely remove. But trying to figure out the sizing and operations of the conveyance project before we’ve established safe limitations on how much water can be removed from the system just doesn’t make sense. It’s a recipe for disaster.”