Via: www.sfchronicle.com By: Tara Duggan

Alarmingly low numbers of baby salmon are surviving their journey down the Sacramento River to the sea, confirming conservationists’ fears that low flows and high river temperatures during the drought would wipe out most of the endangered winter-run salmon born last year.

Only 2.6% of the eggs that winter-run chinook salmon laid in the Sacramento River resulted in fry, or inch-long baby salmon, according to a report from the state Department of Fish and Wildlife made public on Monday. Used to monitor and project the health of the population, this “egg-to-fry” survival rate is the first official estimate of baby salmon born last year and the lowest in the past two decades.

The implication for endangered winter-run salmon is dire, according to conservationists. The fish have only a three-year life cycle, so if they’re wiped out a few years in a row, the population is at risk of extinction.

The report states that the reason for the low survival rate was mainly due to high water temperatures in the Sacramento River, which caused countless eggs to die and hundreds of female fish to perish before spawning.

“The basics is these fish have multiple stages in fresh water and they need to survive all of them,” said Jon Rosenfield, senior scientist at the nonprofit San Francisco Baykeeper, one of several critics of state and federal water management policies.

Last spring, biologists with National Marine Fisheries Service predicted the policies would result in a massive die-off of salmon eggs due to drought conditions.

Named for the time of year they head upstream to spawn after leaving the Pacific Ocean, where they spend two years as adults, winter-run fish are one of several historic runs of Sacramento River salmon that spawn during warm months when the river runs low. Fall-run chinook salmon, the population that is caught by sports and commercial anglers, often faces perils similar to the winter-run because they spawn right afterward, though they’re more numerous.

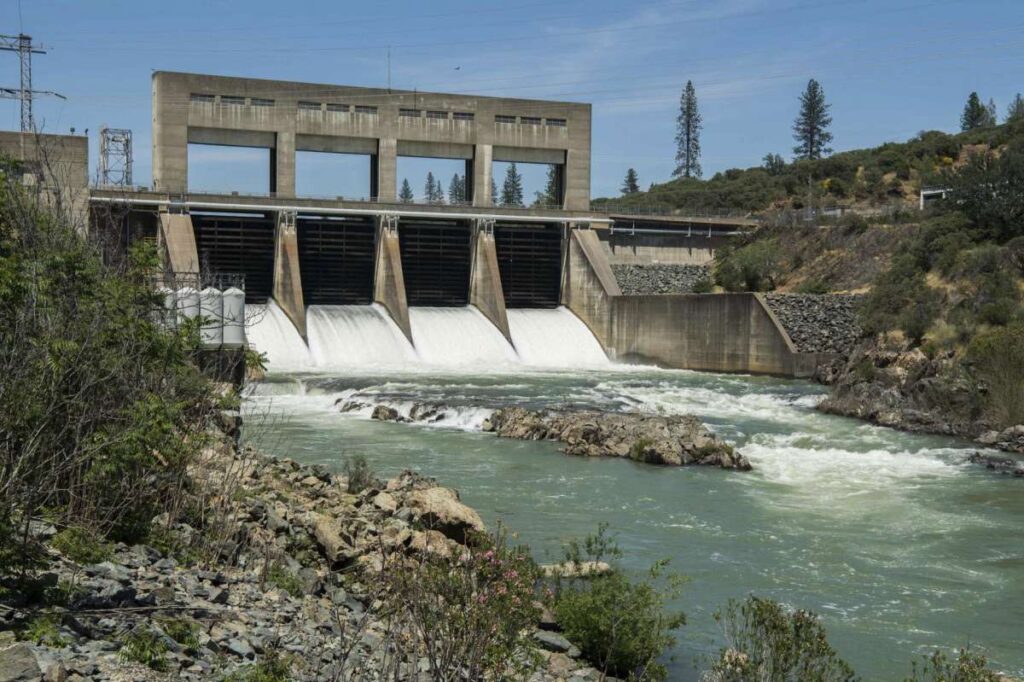

“The hot water that came out of Shasta Dam, flooded the Upper Sacramento basin and killed the majority of winter-run, persisted right into the fall and covered the eggs of fall-run salmon,” said John McManus, president of Golden State Salmon Association. “We probably won’t know for months what it means to fall-run, but there’s good evidence to show that they’re going to suffer a very similar fate.”

Critics blame the die-off on the federal Bureau of Reclamation’s temperature control plan, which is used to determine the timing and flow of water out of Shasta Dam and therefore the temperature of the river at critical stages. They say the plan prioritized senior water rights holders such as large rice farms in the Sacramento Valley, which got a comparatively large percentage of their water allotment last year despite the drought.

Critics also say the state, which has the power to approve or reject the bureau’s plan, didn’t do enough to protect the fish.

“So basically, we have state and federal government agreeing that senior water rights are more important than avoiding extinction of a species,” McManus said.

In a statement, a spokesperson with the Bureau of Reclamation said the plan “was developed in close coordination with federal and state fish agencies and conditionally approved by the State Water Resources Control Board. It provided spring, summer, and fall operations to maximize survival during the poor conditions caused by the current drought.”

The statement detailed other actions the bureau said it took to protect salmon, including an emergency installation of water chillers at the fish hatchery at Shasta Dam, where it also increased production of winter-run chinook salmon for release during the winter, when conditions were better.

Monday’s report from the Department of Fish and Wildlife said another factor was at play in the low baby salmon survival rate: thiamine deficiency.

The problem, which has been observed recently in female fish at the hatchery at Shasta Dam, is caused by a high-anchovy diet that can kill eggs and juvenile fish. Federal scientists think recent unusual ocean conditions off the California coast brought record-high numbers of anchovies to salmon feeding grounds, creating yet a another threat to the imperiled species.

The count of salmon fry is done as the fish migrate down the river past Red Bluff, about 50 miles south of their spawning grounds below Shasta Dam. In 2021, wildlife officials counted 796,403 fry, which is only 2.6% of the estimated 31 million eggs laid based on the number of female salmon they estimate were able to spawn before dying, according to the draft report, which will be updated with final numbers later this month.

The fry continue swimming down the river until they’re big enough to enter the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and then the ocean. Many of the fry will die or be eaten on their way to sea. The Department of Fish and Wildlife estimates only a little over 100,000 will make it to the delta.

The survival of these fish could be threatened further if the powerful state agency responsible for allocating water allows federal and state water managers to loosen environmental rules around water quality in the delta in response to the drought. This could reduce the flow of water in the river, making it harder for the fish to make their journey.

The State Water Resources Control Board was taking up federal and state water managers’ petition to do so at a meeting on Wednesday.

Tara Duggan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: tduggan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @taraduggan