All four California Chinook salmon runs are dependent upon cold water flows and releases from reservoirs for migration and spawning.

California’s salmon industry is valued at $1.4 billion in economic activity and 23,000 jobs annually in a normal season, and contributes approximately $700 million to the Oregon economy and supports more than 10,000 jobs. Industry workers benefiting from Central Valley salmon stretch from Santa Barbara to northern Oregon. This includes commercial fishermen and women, recreational fishermen and women (both freshwater and saltwater), fish processors, marinas, coastal communities, equipment manufacturers, the hotel and food industries, tribes, and others.

Salmon, one of the healthiest and most nourishing foods, have been swimming in California waters for millions of years and have been nourishing people here for at least 14,000 years. Because salmon are anadromous (they spend part of their lives in freshwater and part in the ocean), they require a healthy coastal ocean and inland waters for them to thrive.

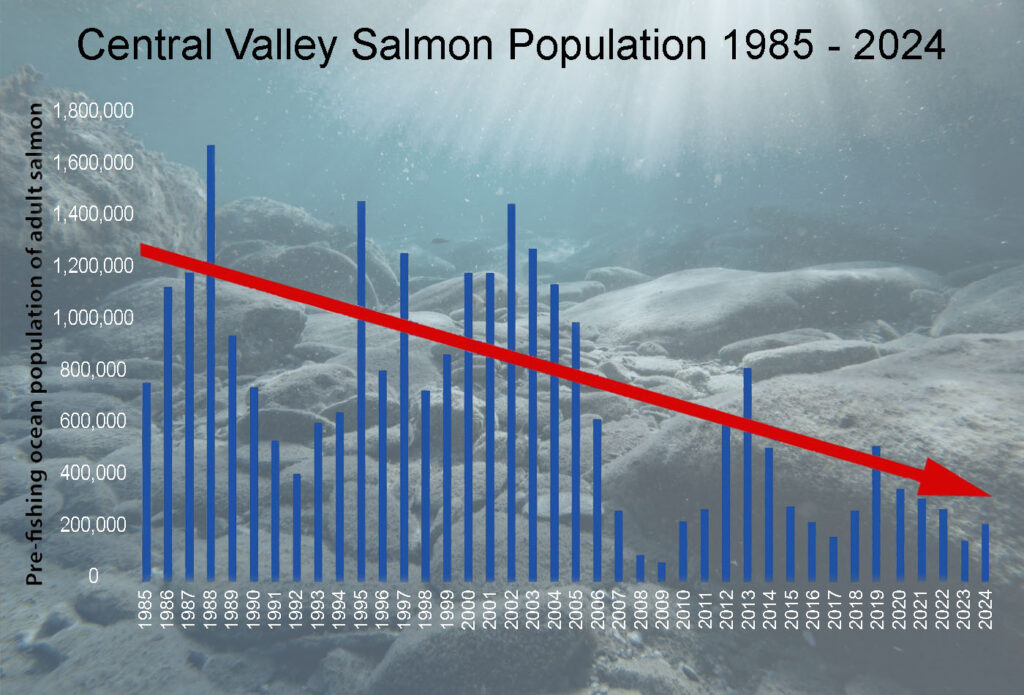

Salmon Problem at a Glance

Competition for freshwater in Central Valley rivers and streams. California engages in massive water diversions, supplying the state’s cities in Southern California and industrial agriculture operations, such as hundreds of thousands of acres of almond orchards planted in arid regions. With this water, salmon need to survive. This is, by far, the biggest single problem.

Rising water temperatures in our rivers. Central Valley salmon try to spawn in rivers that are often too hot to successfully incubate fertilized eggs. River temperatures above 56 degrees kill incubating salmon eggs. When dam operators release cold water from reservoirs for industrial agriculture or cities in Southern California at the wrong time of year, river temperatures rise and kill salmon eggs.

Loss of spawning habitat. When dams were built, Central Valley salmon lost about 80 to 90 percent of their historic spawning habitat.

Loss of rearing habitat. The straightening of rivers and armoring banks with heavy rock, or diking and leveeing, mostly to create farmland, has denied baby salmon access to the banks, edges, side channels, and floodplains where they historically found rich feeding grounds and safe refuge to hide from predators.

Loss of natural turbidity in our rivers and streams. Turbidity created by sediment suspended in runoff provides natural camouflage that baby salmon need to hide from roving predator fish and birds.

Massive water diversion intake pipes dot Central Valley rivers. These pipes suck in untold numbers of baby salmon, some of which end up being deposited in agricultural fields as part of the irrigation water.

A series of massive pumps, strong enough to make the San Joaquin River run backwards, pulls juvenile, out-migrating salmon off their route. The National Marine Fisheries Service estimates that as much as 90% of baby salmon pulled off their natural migratory route to the bay and ocean are lost to predators in the interior Delta or when pulled into these pumps.

The Salmon Problem: A Deeper Look

Competition for freshwater in Central Valley rivers and streams in the form of massive water diversions is far and away the biggest single problem. Loss of habitat is also an issue.

Two years after a wet winter, we have a lot more ocean salmon than two years after a dry year. That’s because plentiful rain and snow runoff boost the survival of baby salmon as they struggle to migrate to sea. When dams were built, Central Valley salmon lost about 80 to 90 percent of their historic spawning habitat. They also lost very valuable rearing habitat in side channels and former floodplains.

California salmon face some challenges in the ocean (typically feed-related) as they grow to become adults. However, the ocean is still mostly doing its part to produce healthy salmon runs.

At the same time, Central Valley salmon rivers were largely straightened, and their banks were armored with heavy rock or diked and leveed, primarily to create more farmland. This denied baby salmon access to the banks, edges, side channels, and floodplains where they’d historically found rich feeding grounds and safe refuge to hide from predators.

Today, dams capture and stop much of the spring rain and snow runoff needed to carry baby salmon from the Central Valley to the ocean. Only in the wettest years, when reservoir operators are forced to release water to prevent over-topping of dams, is there the type of spring runoff baby salmon evolved to take advantage of. (It’s interesting to note that after years of litigation to bring salmon back to the Columbia and Snake Rivers in WA, OR, and Idaho, a federal judge finally granted salmon advocates one wish. They chose to release water from upstream reservoirs in the spring to aid the downriver outmigration of baby salmon every year, and as a result, runs there have rebounded.

Dams and water diversions in our rivers give a heavy advantage to predators that eat baby salmon. Gone too is the natural turbidity created by sediment suspended in runoff that provides natural camouflage that baby salmon need to hide from roving predator fish and birds.

Instead, all too often during spring, rivers run slow and clear, and baby salmon become easy prey for predators.

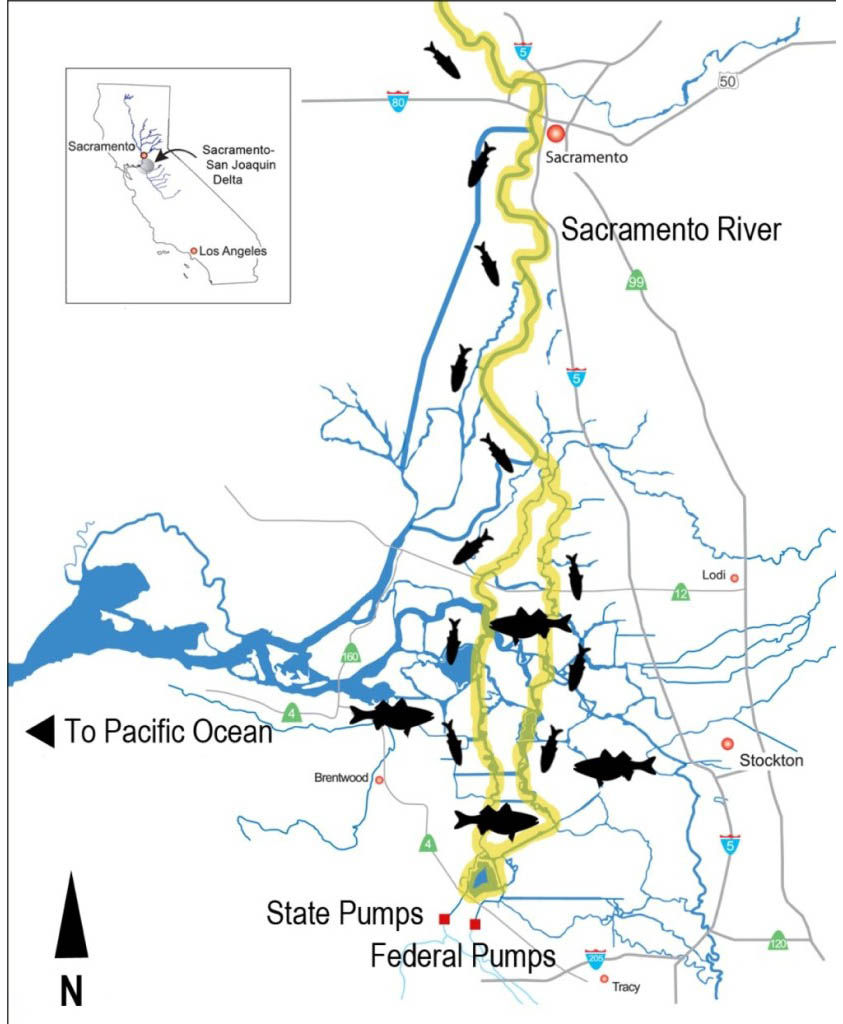

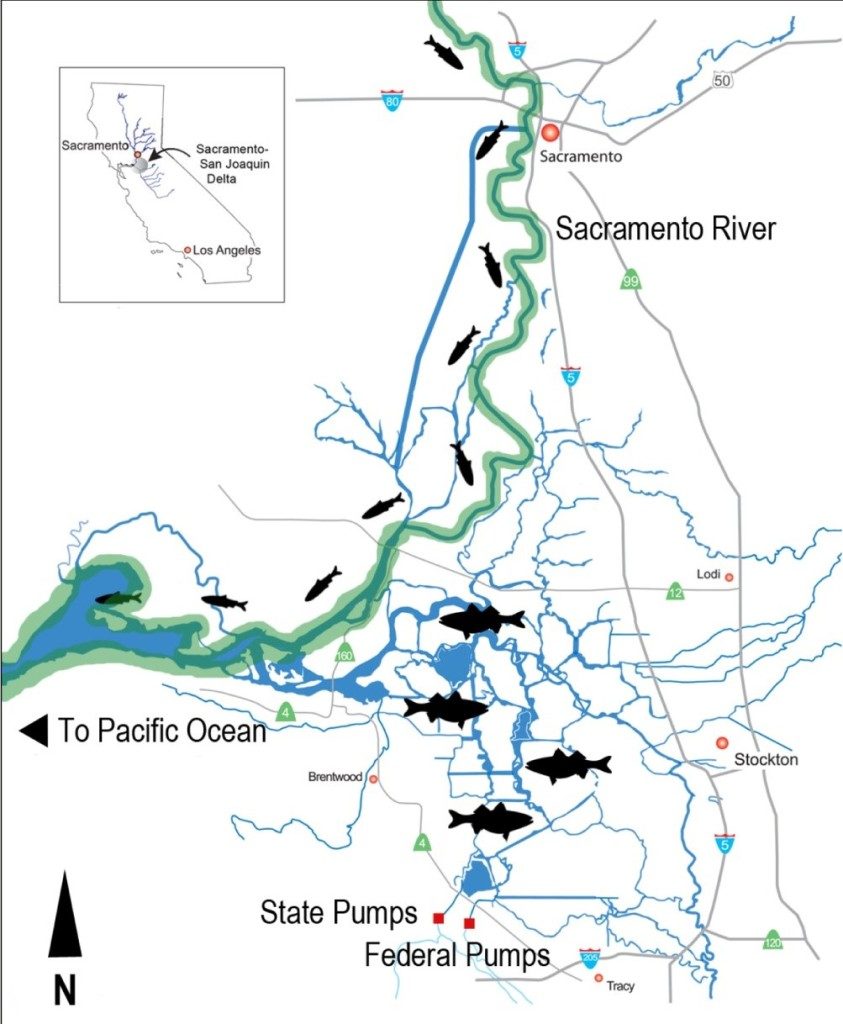

Another big problem for today’s Central Valley salmon is the mammoth water diversions in the Delta. Both of California’s Central Valley major rivers, the Sacramento and San Joaquin, meet in one large Delta some 60 miles east of the Golden Gate Bridge. Decades ago, the state made a decision to tap the Delta waters and export them to southern California cities and to dry lands in the San Joaquin Valley for agricultural use. This decision was made without considering the harm it would cause to salmon. A series of massive pumps is strong enough to make the San Joaquin River run backwards, which pulls out-migrating salmon off their route.

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) recognizes the pumps as salmon killers and, until 2019, required restrictions on pumping to minimize damage to winter and spring-run salmon, both of which are protected under the federal Endangered Species Act. NMFS estimates that as much as 90 percent of baby salmon that deviate from their natural migratory route to the bay and ocean are lost to predators in the interior Delta or when pulled into the pumps. Put differently, for every baby salmon captured at the pumps, up to nine others likely died from the effects of the pumps.

Of the fish captured at the pumps, most are dumped back into the Delta at locations where predatory fish have become accustomed to feeding. Changes in the river bottom throughout the Delta leave deep scour holes where predators congregate and feast on baby salmon. Other problems beset Central Valley salmon.

In today’s Central Valley, salmon try to spawn in rivers that are often too hot to successfully incubate fertilized eggs. River temperatures above 56 degrees kill incubating salmon eggs.

Starting in September and historically peaking in mid-October, fall run salmon lay eggs in nests (called redds). The redds are often left high and dry, and eggs are killed when water managers drastically cut reservoir releases later in the fall when agricultural demand for water is over for the year.

Massive water diversion intake pipes dot Central Valley rivers. They suck in untold numbers of baby salmon, some of which wind up deposited in agricultural fields as part of irrigation water. In recent years, this problem has been recognized, with larger diversions now screened to avoid this loss. However, many more minor, unscreened diversions still exist and are easily visible along the Central Valley rivers.

Human development and competition for water from the Central Valley rivers have been no friend to salmon. However, they persist despite all the environmental destruction around them. There are things we can do to improve it.