Executive Summary

There are over 20 projects in our plan. Immediately below is a summary of the top 10 items on the Golden State Salmon Association’s (GSSA) Salmon Rebuilding Plan. Download the PDF version here.

Historically, the salmon populations of the Central Valley of California reached many millions of fish and were second only to those of the Columbia River in the continental US. Today, some Central Valley runs are nearing extinction. The demise of these iconic fish is an environmental disaster. It is a story of government ignorance, private greed and the gross mismanagement of California’s water resources.

Between 2004 and 2008 there was a large decline in the salmon populations. As a result, in 2008 and 2009 the entire salmon industry was totally shut down to avoid extinctions. This was a major wake-up call and in 2011, the Golden State Salmon Association (GSSA) was formed to develop recovery plans and to advocate for these fish. GSSA has formed such a plan and today, it is actively working to see it implemented.

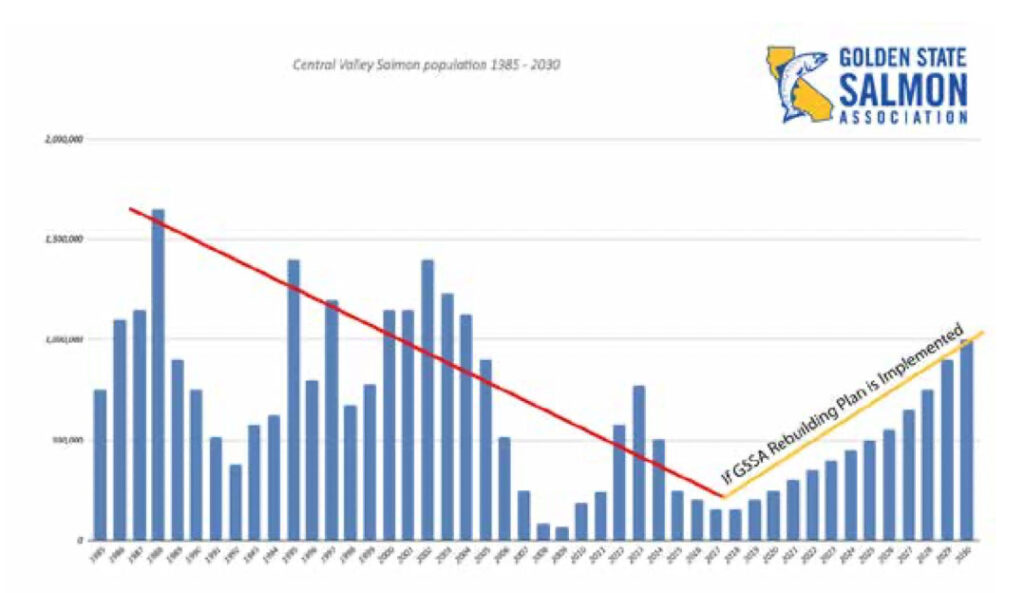

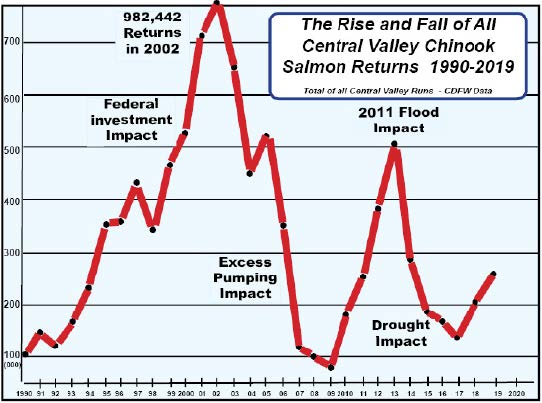

The chart below illustrates a long-term dramatic drop in California’s Central Valley salmon population and a hopeful vision of what the future could be. California’s iconic salmon, which provide $1.4 billion in economic value to California’s economy and supports 23,000 jobs throughout California in recent years is now in danger of a total collapse.

The salmon industry, which includes sport and commercial fishermen and women, seafood processors, restaurants, markets, boat yards, marinas, and others, count on a healthy population of the fall-run salmon, which historically has been the largest. GSSA is working to improve all the runs but we emphasize the fall-run projects that support the 23,000 industry related jobs.

The GSSA approach first looks at the large areas where the current fish are being lost. We then designed or identified projects that will improve survival of both natural spawned and hatchery fish.

We seek stakeholder and government support for the following high priority projects that will make a major difference in the salmon populations.

They will:

• Increase the number of juveniles entering the Delta by 5.1 million fish that currently do not survive by increasing the Sacramento River flows in the early months.

• Add 30 miles of new tributary wild spawning and rearing area in the Feather River and in Battle Creek for the fall, late fall and spring runs, creating up to 20 million new fry annually.

• Increase the survival of juveniles in the Delta by 2.1 million fish by completing the notching of the Fremont weir and opening the migration routes through the Yolo Bypass.

• Increase the survival of the Central Valley hatchery fall-run fish by 2.3 million juveniles by trucking them around the predation and Delta loss areas.

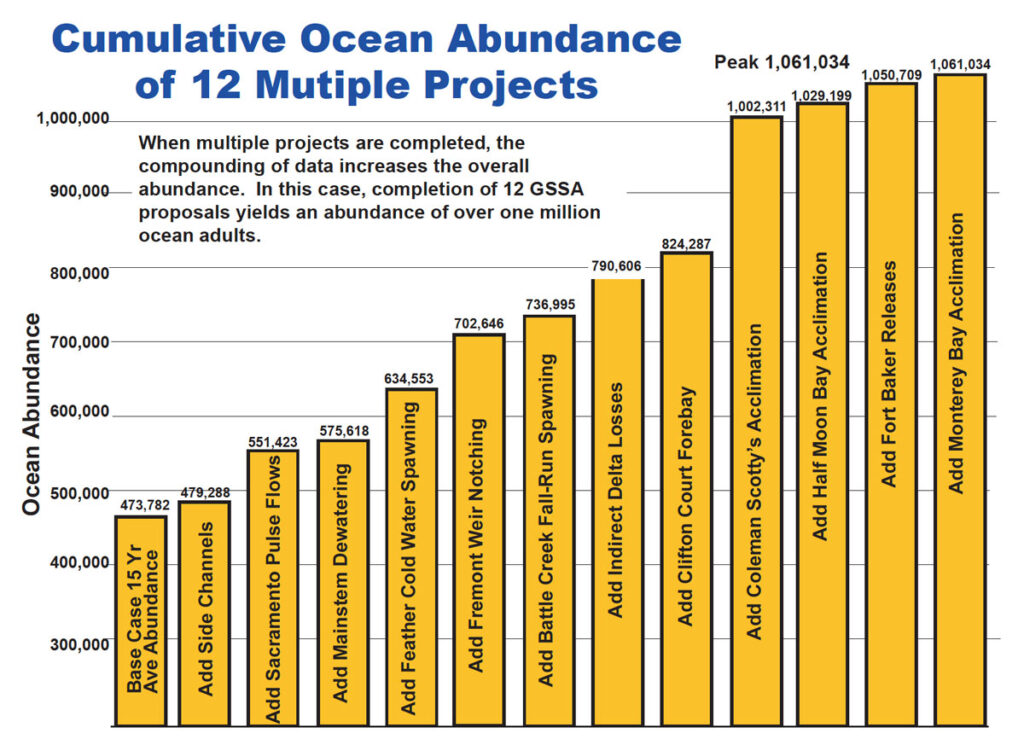

If these projects are completed, the ocean salmon abundance will increase from the current average of 474,000 fish to over 1 million fish. With that, the future of these fish, the fishing industry and consumers will be secure. We urge support for this plan and hope that the citizens of California will once again say “stop, this is not right and we want it fixed”.

Problems, Solutions, Proposed Actions and Results

Wild Fish Problem #1 – Lack of Side Channels

Channelization and rip rapping (armoring) of the Sacramento River have destroyed the shallow edges of the river where juvenile salmon can hide, feed, and rest. The result is heavy predation and low survival, particularly in years with low flow.

Solution – Restore existing shallow side channel zones where the juveniles can hide, feed, and rest.

Action – Continue the Side Channel program initiated by the CVPIA and open additional channels further downstream. Up to twenty sites are proposed.

Results – Three recently restored upper river side channels covering eight acres increased the juveniles entering the Delta by an estimated 939,000 fish.

Read More: Restore Side Channels and Floodplains

Wild Fish Problem #2 – Inadequate River Flows

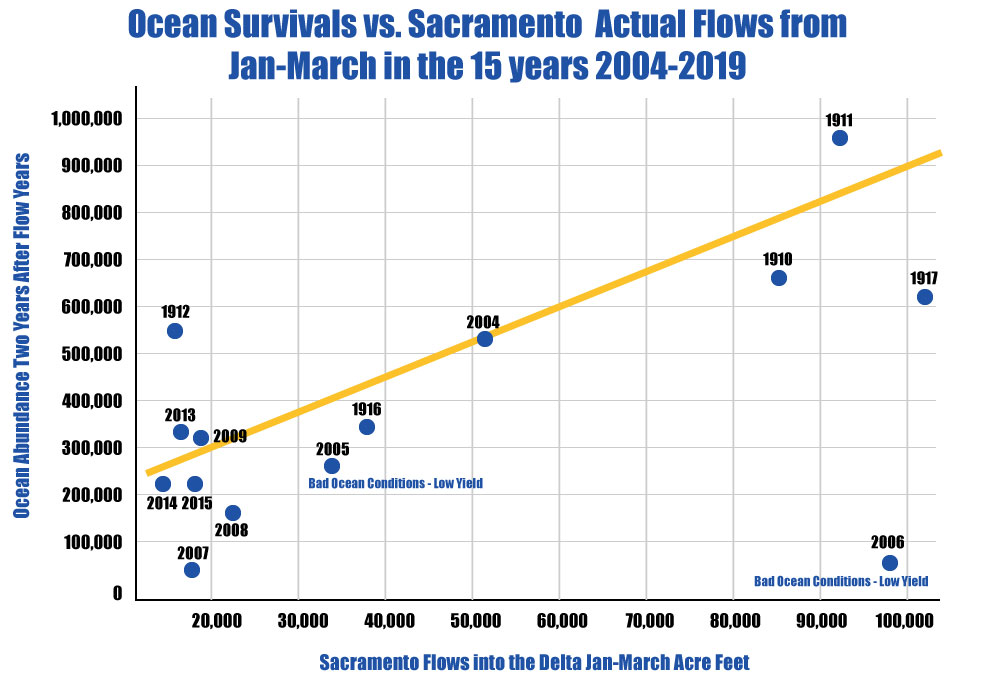

When the Sacramento River flows into the Delta is below 40,000 to 50,000 acre feet during late winter and spring, when the winter, spring, and fall runs are migrating, the runs become unsustainable. The result is continued population declines.

Solution – Provide a minimum of 40,000 acre feet into the Delta during late winter and spring in low water years.

Action – Provide Sacramento River pulse flows reaching 40 to 50 thousand acre feet for the January through March migration period in low water years.

Results – Following the low water and drought years starting in 2007, the average flow of the Sacramento River into the Delta in January, February, and March was 21,000 acre-feet. The average ocean salmon yield from that period was an unsustainable 271,000 fish. Had that flow been 40,000 acre feet, the estimated yield would have been 425,000 fish. The chart below shows salmon survival goes up when the Sacramento River flows to the Delta increase.

January through March are needed to sustain a minimum abundance of 500,000 ocean salmon. Unfortunately, there are too many years that don’t provide that volume of water due to a combination of low seasonal precipitation and upstream diversions.

Read More: Restore Delta Shallow Water Habitat

Read More: Spring Pulse Flows

Wild Runs Problem #3 – Dewatering Fall-Run Redds

Problem – In the fall, the Bureau of Reclamation maintains high Keswick release flows in September and October while the winter-run eggs are in the gravel. During that time, the fall-run fish deposit hundreds of thousands of eggs along the edges of the river. In mid-to-late October, November, and December, the Bureau reduces the flows, stranding the fall-run eggs, which perish.

Solution – Hold the flows steady until both the winter and fall-run fish emerge from the eggs

Action – Either drop the flows before the winter run spawn and then hold them steady until the fall-run eggs emerge, or continue to hold them high until the fall-run fry emerge.

Results – Holding the Keswick flows steady until the fall-run fry have emerged will improve the juvenile fall-run survival entering the Delta by 2.2 million fish.

Read More: Keswick Dewatering

Problem # 4 – Lack of Feather River Spawning and Rearing Habitat

Problem – The fifteen miles below the Feather River Thermalito outlet are currently unusable for the fall and spring-run spawners because the water is too hot for spawning and rearing.

Solution – Implement the FERC Oroville Dam Re-licensing Settlement agreement, which calls for modifications that will provide cold water from Oroville Dam to the 15-mile zone.

Action – Continue working with DWR and other stakeholders to select a final preferred alternative water bypass to replace the hot water from the Thermalito Outlet and to help obtain the necessary permits.

Results – Completing this project will result in an additional 9.9 million additional spring-run and fall-run juveniles entering the Delta. That would be a significant accomplishment for the two runs.

Read More: Feather River Temperature Improvements

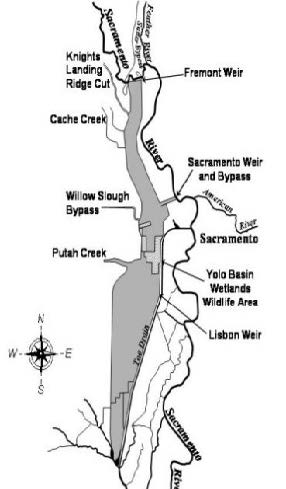

Wild Runs Problem #5 – Delayed Fremont Weir

Problem -The Fremont Weir in the Yolo Bypass is being notched so that more water and juvenile salmon can pass through the bypass, get the growth benefit, and then exit at Chipps Island in the Delta. The juveniles that pass through the Bypass will avoid the high direct and indirect losses currently occurring in the Delta.

Solution – This complex project involves multiple components, including permits, landowner approvals, and construction. Fast-tracking the juvenile outmigration part of the project will yield significant benefits for salmon at early dates.

Action – Encourage parties to finalize landowner flood easement agreements and construct the Big Notch, then start operating it.

Results – This project is one of the leading opportunities to enhance the survival of all four Central Valley salmon runs. Assuming 20% of the Sacramento River outmigrants will pass through the Bypass, the juvenile fall-run population at Chipps Island will increase by 2 million fish.

Wild Runs Problem #6 – Loss of Fall-Run in Battle Creek

Problem – In some return years, up to 80,000 adult fall-run fish enter Battle Creek and the Coleman hatchery. Generally, returns over 40,000 are destroyed as surplus to the hatchery’s and creek’s brood stock needs. In the last twenty years, 50% of all the fall-run returns above Red Bluff now enter Battle Creek instead of moving further upstream.

Solution – Consider allowing fall-run fish in excess of 40,000 to spawn upstream of the Coleman hatchery but below areas reserved for listed spring and winter-run. We could roughly double the amount of available spawning habitat in upper Battle Creek simply by removing the rock barriers below the Eagle Canyon Dam and operating the fish ladder and diversion screen at the dam. A segregation weir installed on Battle Creek somewhere above the hatchery could be operated like Clear Creek is today. In years when fall runs are allowed upstream, the weir would be closed in September to protect spring and winter run spawners further upstream, thus preserving a significant stretch of Battle Creek for the listed fish.

Action – First, work at the federal level to complete the removal of the rock barriers. Second, resolve the issue with PG&E and other stakeholders regarding the operation of the diversion screen and fish ladder at Eagle Canyon. Third, adopt a design and operation plan for a seasonal removable segregation weir upstream of the hatchery to allow additional fall-run spawning and rearing.

Results – This project could be a major contributor to the rebuilding of the upriver fall and late fall runs. For example, 15 miles of prime new fall-run spawning area would add an estimated 3.4 million fry to the upriver production.

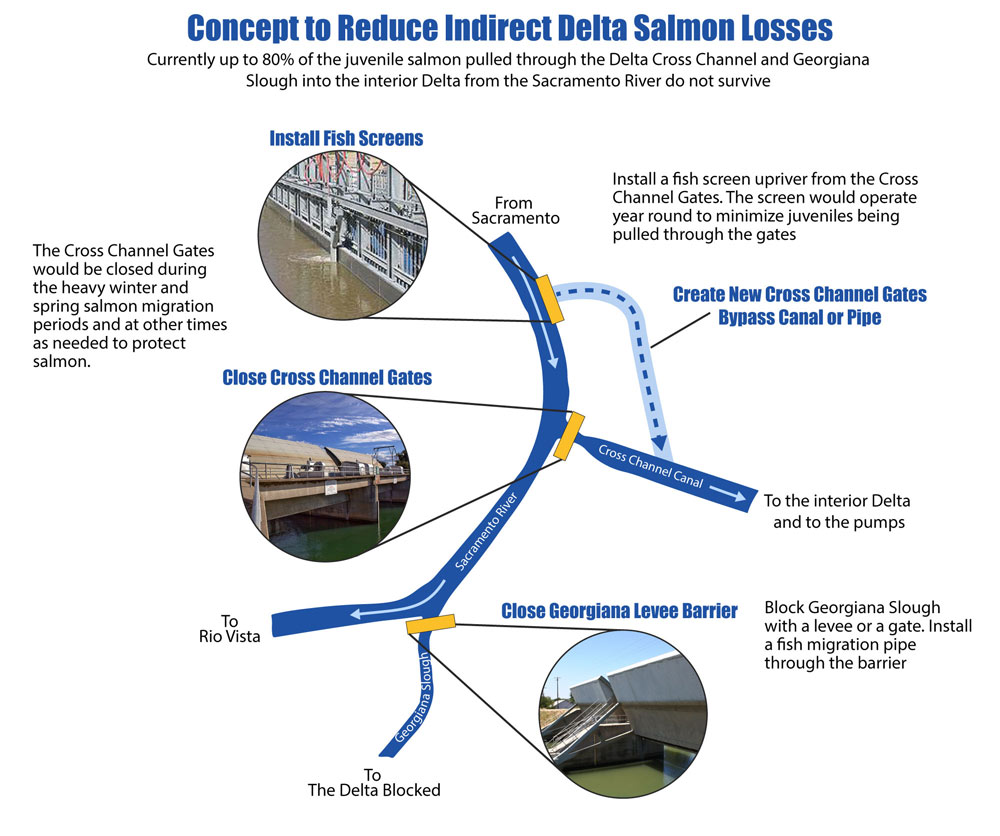

Wild Fish Problem #7 – Indirect Delta Losses

Problem – Currently, up to 80% of the Sacramento River juvenile salmon entering the South Delta through the Cross Channel gates and Georgiana Slough do not survive. Disorientation, high temperatures, lack of suitable habitat, and predation all take a heavy toll. This is a significant salmon problem in the Central Valley system, and on average, it destroys approximately 10 million juveniles annually.

Solution – Once the fish are in the South Delta, there are few, if any, survival options. To solve this problem, steps must be taken to prevent the juvenile salmon from leaving the Sacramento River. Alternates include:

Barriers to force more juveniles into the Sutter and Steamboat sloughs.

A fish screen a few miles upstream of the gates and a diversion canal moving the screened water into the existing canal below the Cross Channel gates. Then block the Georgiana Slough and close the Cross Channel gates when the juveniles are migrating.

Action – Undertake an evaluation of the location and design of a fish screen and a bypass canal. Any solution will have to preserve or enhance existing Delta Outflows.

Results – This is a significant undertaking, but it fixes the severe loss problem that has existed ever since the Central Valley Project was designed. The fish must be separated from the water diversions. Screening is the only practical way to do this. Reducing the loss to 50% would save 2.9 million juveniles. See the diagram on the next page.

Wild Fish Problem #8 – Losses at Clifton Court Forebay

Problem – Clifton Court Forebay is a 2,000-acre lake that supplies water to the State Water Project’s Banks pumping plant. It has long been known as a significant loss location for juvenile salmon from the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers. In 2013, DWR completed a study of salmon predation losses in Clifton Court. The conclusion was that 83% of the juveniles were lost to predation before they got to the pumps. This amounts to an estimated 2 million lost juveniles annually, including ESA-listed endangered species. DWR has made several attempts to remove predators, but none have been successful.

Solution – One option: Drain the lake and remove most of the weeds and other predator habitat. Fill the shallow areas and convert the main channel to a faster-moving canal without predator resident areas. Fill the scour holes near the radial gates to reduce the number of resident predators.

Action – Conduct an evaluation or a scientific study to refine the strategy for removing the predator habitat.

Results – Reducing the loss to 50% would save 717,000 juveniles.

Read More: Clifton Court Predation

Hatchery Fish Problem #1- High Loss of Upriver Coleman Fish

Problem – The Coleman Hatchery releases approximately 12 million fall-run smolts annually from the hatchery on Battle Creek near Redding. The NMFS Santa Cruz Science Center studies indicate that in low-flow years, up to 70% of these fish are lost to predation in the first 80 to 100 miles of the Sacramento River. This amounts to 6 or 7 million lost smolts, which seriously damages the overall survival of the Coleman hatchery fish in low-flow years.

Solution – The US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Golden State Salmon Association, and the Bureau of Reclamation are testing a system of trucking Coleman smolts around the predation zone to release sites downstream. They will be acclimated in net pens at that location. The test ran for three years, and the results are now being analyzed.

Action – If the data indicates the test was successful, expand the numbers released and put the system into regular use, at least in low-water years.

Results – If the program is successful and expanded to 2 or 3 million Coleman smolts, it would add up to 5 million additional juveniles into the Delta in low-flow years.

Read More: Modify Coleman Hatchery Release Practices

Hatchery Fish Problem #2 – Increase Acclimation at Half Moon Bay

Problem – The salmon industry and its customers are very dependent on the state and federal salmon hatcheries in the Central Valley. Initially, the hatcheries released all their juveniles at the hatchery locations. Unfortunately, as water demands increased, the river and Delta hatchery losses also rose. Some of the runs became unsustainable. To offset these losses, in 1990, some hatcheries began trucking smolts to sites in San Pablo Bay, and today, more smolts are being trucked directly to ocean saltwater. That has increased the hatchery survivals from frequently less than 1% to 3% and, in some cases, even 4%, which produces strong, sustainable results. The Coastside Fishing Club, located in Half Moon Bay, has been a leader in developing this technology.

Solution – Continue testing and developing this direct saltwater technology.

Action – Work with willing partners to increase the number of smolts released at Half Moon Bay’s saltwater gradually from the current 750,000 annually to 2 million. Some would be acclimated, others might be directly released.

Results – Making this transition will increase the survival of ocean adults by 27,000 fish.

Hatchery Fish Problem #3 – Increase Releases at Fort Baker

Problem Situation – Fort Baker is another saltwater ocean release site next to the Golden Gate Bridge. In this case, the smolts are released directly into the water without the use of net pens. The releases are made in the evening after the bird predators have quit for the day. They are also released on outgoing tides. The survivals here are also reaching 3% to 4%.

Solution – Continue testing and developing this direct saltwater technology.

Action – Gradually increase the numbers released to 2-4 million.

Results – Making this transition will increase the surviving ocean adults by 22,000 fish.

Hatchery Fish Problem #4 – Low Populations in Monterey Bay

Problem – Juvenile fish are now being released in Monterey Bay, at Santa Cruz and Monterey, directly into the ocean after nightfall to eliminate bird predation. In the near future, each site will acclimate 240,000 smolts annually.

Solution – Continue testing and developing this direct saltwater technology.

Action – Gradually increase the number of fish acclimated.

Results – Completing this project will increase adult ocean survival by 10,400 fish.

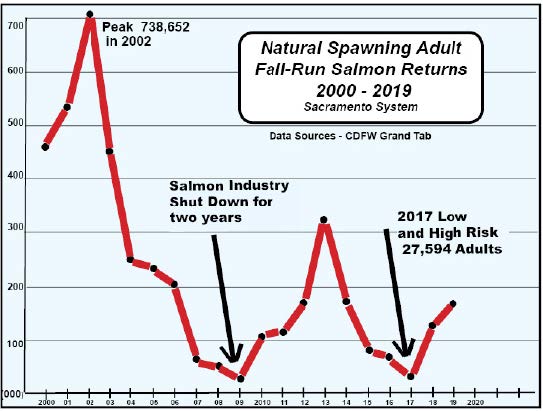

Salmon Status Total Central Valley

In the late 1980s, a severe drought occurred. That, and other factors, caused a significant crash in all four of the Central Valley salmon runs. By 1990, the population of the winter-run had dropped to only 191 spawners due to losses at the Red Bluff Diversion Dam. It was listed under the Endangered Species Act as Threatened in 1989 and Endangered in 1994. The Federal Government then spent $1 billion attempting to address the problems in the Sacramento River, and by 2002, a modern record of 944,673 salmon had returned to spawn in the Sacramento River. The total Central Valley returns that year were 982,442. Meanwhile, water diversions from the Delta increased by about 16 percent starting in 2000. Between 2000 and 2006, three all-time high water diversion records were set, causing severe damage to the salmon runs.

In a 2004 federal political action, most of the pumping restrictions were eliminated or weakened, and the water delivery operations virtually ignored the needs of the salmon. The runs crashed. In 2008 and 2009, all salmon fishing was shut down to avoid an ESA listing. In 2009, some pumping restrictions were restored, which helped improve the returns in 2012 and 2013. A few years later, drought hit.

In 2019, the Trump Administration again eliminated virtually all the salmon. Extinctions could result. GSSA and others filed a lawsuit in an attempt to overturn that policy.

Currently, the only times the salmon populations begin to recover are in flood years. The floods in the spring of 2011 swept the migrating juvenile salmon past all the predation in the Sacramento River and past the Delta pumps and into the ocean. This yielded over 400,000 fish by 2013. Unfortunately, the runs then dropped again in 2017 to a near all-time low.

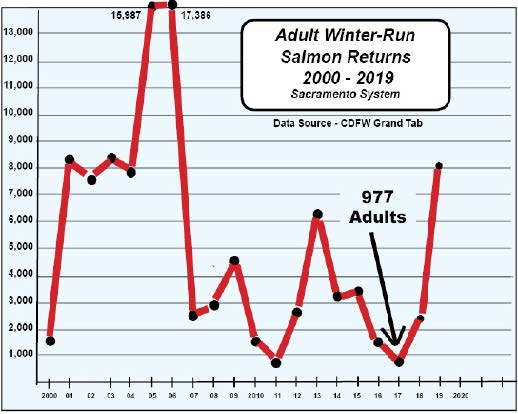

Salmon Status Winter-Run

In 1990, only 191 adult winter-run spawners returned to the Upper Sacramento River. The run was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1989. It was elevated to Endangered in 1994. The Federal Government then spent $1 billion fixing problems in the Sacramento River. This run, along with all the other runs, responded, and by 2006, this population had reached 17,386 returns. Since then, it has been mostly downhill. The run is now struggling, and in 2017, it hit a low of only 977 returns. A conservation hatchery (Livingston Stone) was constructed in the upper Sacramento River to protect the gene pool. Winter-run have also been reintroduced in the upper Battle Creek watershed.

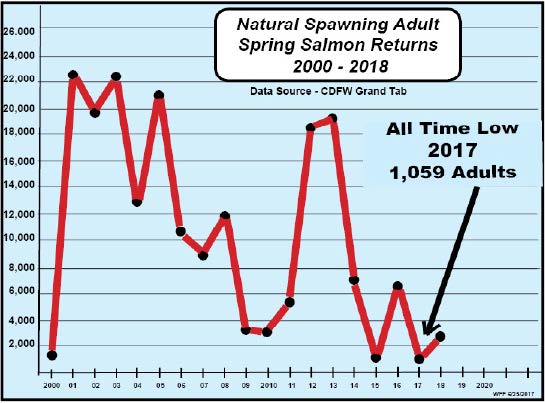

Salmon Status Spring-Run

The natural spawning spring-run mature adults migrate from the ocean in the springtime. They migrate to cold water tributaries of the Sacramento River, where they can survive the summer heat. They then spawn in the fall. In high runoff years, they do well, but in low-flow years, survival is low. The chart is a good example of the importance of high river flows. The floods of 2011 resulted in a recent record return of the species in 2013. Then, due to the drought, the run hit a record low in 2017, with only 1,059 fish. This fish was listed as threatened in 1999 under the Endangered Species Act. Recovery has been difficult. Increased outmigration flows in some high-elevation tributaries appear to be a key factor in improved survival. These fish are also now allowed to pass the barrier at the Coleman hatchery and spawn in upper Battle Creek.

Salmon Status Fall-Run

In recent decades, the fall-run has been the most abundant species, and it is the run that commercial and sport fishermen traditionally harvested. However, between 2002 and 2009, the run declined by 60% from a high of 835,000 Sacramento natural spawning and hatchery fish in 2002 to a low of 50,000 in 2009. The natural spawning (wild) portion of the run dropped from 739,000 to 29,000 fish. In 2008 and 2009, all salmon fishing was halted due to low fall-run abundance. The only time this run now improves is when flood years, such as 2011 or 2017, push the juveniles past the river and Delta losses.

The salmon fishing industry and salmon production are in serious trouble. In recent years, two-thirds of the commercial fleet has been lost, along with thousands of jobs. The economic impacts have been similar for the charter fleet, recreational fishermen, hundreds of fishing businesses, and the California coastal communities. The fall-run has been mostly ignored by the agencies in favor of the ESA-listed species. The Golden State Salmon Association has a rebuilding plan, but it needs funding and implementation.

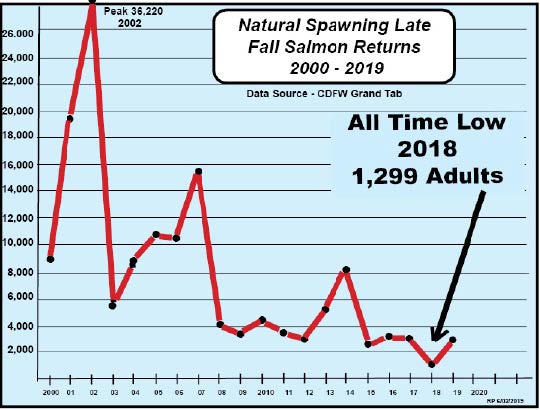

Salmon Status Late-Fall Run

The late-fall Central Valley Chinook salmon are the largest of the four Central Valley runs, often reaching 35 to 40 lbs in size. Fishermen prize them. Its population has steadily dropped, and it is now approaching an extinction risk. In eight of the last ten-year classes, the number of natural spawners has been below 4,000, and in 2018, the population reached an all-time low of only 1,299 fish. The only time that its survival increases is following flood years. This fish desperately needs recovery actions to avoid irreversible decline, but it has been largely ignored by fish and water agencies. The Golden State Salmon Association has some rebuilding proposals, including improved river flows and the development of additional spawning areas in Battle Creek. Absent aggressive government actions, there is a high risk that this run will continue to decline until it is totally lost.

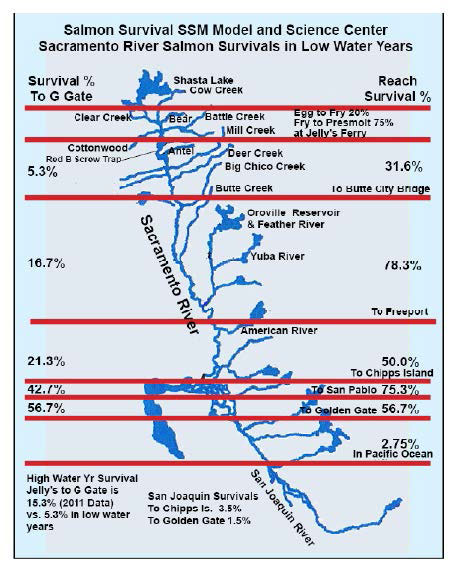

About the GSSA Salmon Survival Model

The GSSA Salmon Survival model is used to evaluate the contribution of flow and habitat projects aimed at improving the survival of downstream migrating juveniles in the Sacramento River. It is a structured decision model with abundance as its primary objective. It was originally developed in 2015, relying heavily on data produced by the Santa Cruz Science Center. Each year, the Science Center releases acoustic-tagged juvenile salmon in the upper Sacramento River and then tracks their survival in 17 reaches to the Golden Gate. The survival model contains this Science Center data, summarized into seven reaches. Since most of the juvenile salmon are lost in low-flow years, the initial model was based on the low-water years of 2007, 2008, and 2009. Modifications to evaluate higher flows were built in later. The 7 reaches are:

1. Sacramento River above Jelly’s Ferry, 2. Jelly’s Ferry to the Butte City Bridge, 3. Butte Bridge to Freeport (entry to the Delta), 4. The Delta to Chipps Island, 5. Chipps Island to San Pablo Bay, 6. San Pablo Bay to the Golden Gate and 7. The Golden Gate to mature ocean adults

The model begins with a Base Case based on the 15-year average of adult returns, hatchery releases, and other relevant data from 2004 to 2017. The model uses that data to calculate the base population at each reach and an ocean abundance of 473,782 mature adults. Improvements can then be measured from that base.

A project under consideration is first estimated in terms of the new salmon juveniles it will produce or the number of existing fish it will save. That data is then put into the model, and the downstream results can be seen at each reach and finally as mature adults in the ocean. SDM judgments can then be made as to the best projects. The results from this model closely parallel the results from the SIT DSM model.

Each of the twelve GSSA projects was run through the model, and the survival gains are expressed in different ways and at various stages. The total number of fry generated in the Base Case was 62,175,989. These generated 473,782 base case mature adults in the ocean. That is a survival of 0.76% which is very low and unsustainable. The cumulative twelve projects generated 1,051,034 adults in the sea, which represents a 1.69% survival rate. That represents a reasonable and sustainable population.

Current Survivals

The Santa Cruz Science Center has been studying the survival of salmon in the Sacramento River since 2007. They release batches of acoustic-tagged Coleman smolts at Jelly’s Ferry in the upper river and then track them in 17 reaches to the Golden Gate. The map on the right shows a summary of the results in the reaches for 2007, 2008, and 2009. Those years were low-water years, and survival rates were low. The figures down the right side show the survival in each reach. The figures on the left show the survival for each reach to the Golden Gate. For example, the survival rate from the upper river reach is 5.3%. That means that if 1,000 fall-run juveniles were released in the upper river, only 53 of them would reach the Golden Gate. The average survival in the ocean is then 2.75% which would result in only a little over one survivor (1.45 fish). Bottom line, the current low water survivals in the Sacramento River are extremely low and do not produce sustainable runs. The San Joaquin survival is near zero. This makes recovery there very difficult.

LINKS TO DESCRIPTIONS OF SECOND TIER PROJECTS AND ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

Habitat Restoration

Increase Access to Yolo Bypass